Andy Hooper talks about his experiences of moving to a new Head of Product role…

“Product Management is the hardest job in tech. It is impossible to fully please anyone … and you disappoint pretty much everyone at some point.”

So exclaimed my colleague Johan Bolin (below) at Edgeware AB, a 150-person technology vendor based in Stockholm. I had direct experience in product management, so I knew he wasn’t just exaggerating for effect. I’d experienced this myself on many occasions.

Nonetheless, I confess to some feelings of apprehension after he said it; as the incoming Head of Product, taking that role for the first time, I wondered if there was something about this company that amplified the challenge.

… so was this comment justified?

As it turned out, there was nothing unique about Edgeware. The dynamics that drove Johan’s observation are very common in product management.

Understanding the factors that plausibly make product management the ‘hardest job in tech’ is essential if we’re to improve our planning and decision-making as Product Managers and Product Leaders.

Pulled in Many Directions at Once

Let’s start by understanding the somewhat unique position that Product Managers occupy and the different roles that need to be played by the ‘perfect product manager.’ Then we can consider the effective frameworks and tools that might be used.

Consider the flow of information in a typical company. The collaborative effort of many teams is driven by communication:

- Formal and informal

- Verbal and written

- Process-driven and ad-hoc

- Instruction and request

Teams that collaborate more with other teams will have a harder time balancing their internally generated work with requests from external stakeholders. They’ll need to continually make judgment calls (conscious or not) about what to spend time on. Some teams have a work backlog that is relatively homogeneous, but others are more ‘central’ in terms of how information flows and must deal with more variety.

So, which teams tend to be the most connected teams in a typical company and are, therefore, most likely to have this challenge?

One study undertaken by Miro, found that the CEO’s office is the ‘most connected’ team. Product Managers closely followed, confirming the suspicions of many in the profession!

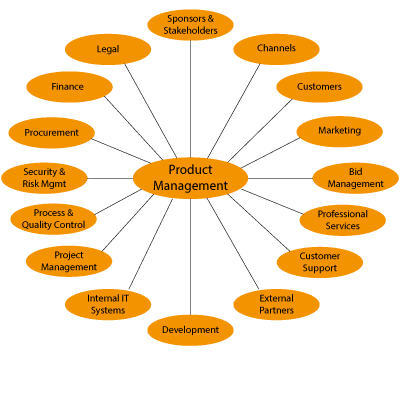

This intuitively makes sense. Product Managers typically interact with a wide range of touch points in larger organizations as they develop business cases, launch products, and fix issues:

- On the market-facing side, PMs interact with customers, users, sales and marketing teams, and the broader industry. The technical context of the domain, the customer problem space, and the competitive landscape all influence important decisions on product strategy, roadmap, and feature value. These stakeholders rely on PMs to support them with industry, domain, and product expertise.

- On the delivery side, engineering and operations teams have a constant need for product direction, explanation, context, and clarity. They rely on the work of the PM to ensure that they are building and delivering the right product. They need insight into the usage and context of their software in the target market and expect the PM to be responsive and supportive of this need.

- Time must also be spent with marketing, finance, and leadership teams to ensure their goals and interests are represented appropriately (“lead conversion is too low! We can only improve it if we enhance the free tier!”)

With so many stakeholder interactions to manage, it can be difficult to carve out time to focus on what might be considered the core of the Product Management role: ensuring the ongoing viability and feasibility of products with valuable outcomes for customers and users.

Product Managers find themselves at the center of things, to say the least.

The Domain Expert Trap

As a hub of many information flows in the company, Product Managers can build a body of knowledge that is matched by few others. This may well lead to stakeholders using the PM for myriad jobs – the more one knows, the more in demand one is.

Called upon to provide clarity and insight in all directions, a backlog of support requests starts to build, and other work lies unattended. Inevitably, Product Managers in this situation may find themselves neglecting less immediate tasks. And these tasks may well relate to crucially important questions that help increase the longer-term probability of success for the product.

If you are a PM who is focusing too much on immediate support requests and firefighting, then there’s a risk you can end up in a product management ‘pathology’ that I call the Domain Expert Trap.

A crucial part of the PM’s success is to be credible with customers and stakeholders. Credibility is built on knowledge, expertise, and experience in the technical, commercial, and industry domain while being effective in applying that to our customer problem space.

Unfortunately, if we don’t pay attention, then just being the domain expert can consume every working hour. And strangely, this trap can be a comfortable place to settle. Overwhelmed PMs can find solace in the fact that their domain expertise is of significant value to stakeholders and customers, who continue to provide reinforcing feedback and positive messages. Newer PMs can be eager to please and want to establish relationships and credibility, which tends to be forthcoming while sitting in the trap.

This all comes at a cost. Without the conscious attention of the PM themselves and coaching and support from their leadership team, it’s easy to become stuck in the trap of those reinforcement loops. The longer this goes on, the harder it is to rebalance and the higher the risk to product viability in the medium and longer term.

Dealing with these Challenges

So ‘immediate and urgent’ demands risk crowding out more forward-looking product management work. With the Domain Expert Trap also lurking around every corner, what techniques can PMs employ to achieve a better balance?

I’ve often found that the first important step to take is to consciously move from reactive to proactive in personal time planning. Simply put, PMs should deliberately decide how much time to spend across each of the categories that make up the overall ‘craft’ of Product Management, both in immediate work and ongoing development. This helps to explicitly allocate time in the working week in the right proportions.

Of course, it’s not an exact science. But the very exercise itself often helps to start changing the approach and mindset of the PM and moving things in the right direction.

The team at Product Focus has distilled the PM role into four main categories of work, and I find this model very helpful as a starting point:

From ‘Leading’ – Product Focus journal

Effective PMs perform their roles in a way that means their time is allocated appropriately with execution and personal development across each of these categories:

- Knowing what to do spans the specifics of the technical, commercial, market, and industry environment of the company as well as the general product management skills required to establish the feasibility and viability of the product in the marketplace.

- Being able to get things done incorporates a set of skills, knowledge, and behaviors that span from the immediate company operating environment to the soft skills required to persuade and influence others through indirect leadership.

Note that although the boxes in the graphic are the same size, that does not mean they will always have equal weight in your situation. On the contrary, the appropriate weighting of each will be quite specific to the individual circumstances of each PM.

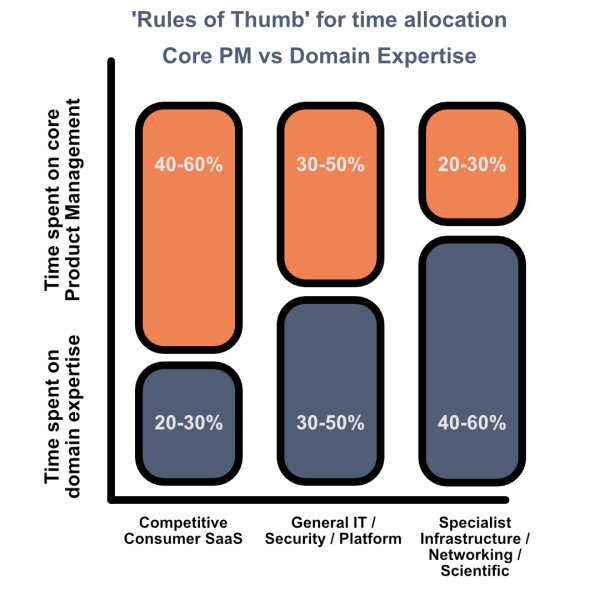

So, just how much domain knowledge is ‘enough’ to deliver the needed credibility? How much time should be spent in the top left box?

The answer to that will depend on the company, but the following model may help to frame the judgment call.

- Products that are heavily scientific or technically oriented, especially in B2B domains, are likely to need a higher degree of technical credibility in the PM. The recruitment and coaching process for such PMs is likely to place a correspondingly higher value on prior domain expertise.

- Products that are built in a more generic way and/or solve more common sets of customer problems may not need quite as much specific domain expertise. Recruitment and coaching can focus on more transferable product management and soft skills.

- In the above table, the balance of time will be spent on personal development, training, and general administration.

There can also be a lifecycle aspect to consider here. In the early days of launching a new product, it may be that the launch team and PM must dedicate a greater proportion of their time to questions, clarifications, and provision of expertise. Then, once a product reaches some level of maturity, it is usually appropriate to find other ways to educate and inform stakeholders on the details while shifting attention to the aspects of product management that will ensure overall viability and success.

What can Product Leaders do?

I’ve often seen overworked Product Leaders falling into the trap of becoming too directive with their team members, which can add to their team’s time management challenges. Coaching and supporting their team members may be a better approach in this overall transition towards a more explicit allocation of working time.

Here are just two further possible leadership considerations out of the many we could discuss.

Organization Planning and Design

There is a large body of work available to help with the creation of effective organizations, but in some companies, not enough time or resources are available to make good use of it. In those cases, organization design work can be limited to the production of an org chart and deciding who reports to who. If you’re in this situation, your teams will probably thank you for spending some quality time assessing how to improve.

The words that we assign to job titles, and the low information variety of lines on an org chart, do far too little to capture the essence of an effective organization design. A rich set of tools is available to help us to better capture the depth of interactions, roles, and responsibilities. If we do this well, then we will have roles defined that clearly link the goals and objectives of everyone to the overall company direction, giving teams the clarity they need to make daily priority calls on how to spend their time effectively.

At the very least, models such as the Product Focus ‘Product Activities Framework,’ and the PM effectiveness chart above can be used to provide a more complete set of work categories for assignment across our teams.

Coaching and Support

Even if a Product Manager spends time to consider what their effective time allocation should be, this may well be wasted time if their leadership team hasn’t put together a clear organization design in which they can operate. And nothing is static: it’s an ongoing conversation to support PMs in the ongoing assessment of where they spend their hours and how they find the right balance.

I’ve found two resources particularly useful in improving my own approach to team mentoring and coaching:

- The guidance in the book ‘Empowered’ by the Silicon Valley Product Group is insightful. The most effective product companies prioritize coaching by product leaders as a primary activity – not just an annual event. The authors do a particularly good job of establishing a mindset that can help drive the right leadership behavior.

- The tools and approaches of Situational Leadership are helpful in determining the right style of coaching for different PMs at different levels of experience. The training establishes a model of ability vs. motivation to help leaders to determine which style will likely work best in moving team members’ performance in the right direction.

Leaders should always be wary of the ongoing risk of PMs falling prey to the ‘Domain Expert Trap’ and set up mechanisms to detect and correct when this seems to be happening. In the very short term, urgent and immediate tasks might be all a PM should do. But make this decision deliberately and don’t allow it to continue for too long.

View from Outside

During the preparation of this article, I canvassed opinions from my professional network. I wanted to glean a sense of what stakeholders outside the product team view as the traits of the most and least effective PMs.

Here are a few summary observations from B2B professionals:

“Effective = true partners to presales and sales;

ineffective = hidden behind processes.”

“It’s common to have unclear role descriptions or simply unrealistic expectations where all peers (sales, R&D, marketing, operations, finance) expect the PM to be an expert and know the answer to all the questions they have.”

“The PM doesn’t necessarily have to be a domain expert when starting but must be curious and with the ambition to become the expert. Meaning spending time learning the market, the products and spending time with all peers, including those that are not necessarily the closest or loudest ones.”

It seems that many stakeholders do indeed expect PMs to be superhuman! Joking aside, it’s clear that the drive to be responsive and to be seen as an expert will continue to be a major factor in driving PM behavior. Therefore, product leaders can also play an important role in helping the stakeholder community appreciate that some critical product management tasks are less visible to them and must also be done to deliver meaningful results over the longer term.

A final thought. Ling Koay gave me a comment that I like very much – she focuses on the need to connect a longer-term vision with day-to-day actions. Plenty to reflect on here:

“The best PMs are the ones who are visionary, show a strong commitment to their visions in day-to-day actions, and are excellent listeners. They are strategic in decision-making by always considering the impact of their decisions from three perspectives – commercial, technical, and operational. How this gives us more business, how it impacts the build and roadmap, and how it affects the team. The exceptional ones can articulate their vision in many ways and formats, ensuring the message is understood and consumed by all the different personalities and preferences of the people they interact with – be it the buyers, the users, or their co-workers.”

Andy Hooper has been working in product, presales, and business development roles for the last 20 years, specializing in video and streaming technology.

Via his consulting business, he now works with a team of professionals to help companies to improve their product alignment: improving the coherence of their product, presales, and sales efforts through an independent, honest assessment of the current situation and identifying opportunities for improvement.

Leave a comment