The prime objective of a business case is to persuade senior management to invest the company’s money, time, and resources in your investment project, rather than in a competing one. Business cases come in all shapes and sizes, whether you’re developing a new product, justifying the next version of an existing IT system, or aiming to explain the rationale for buying up another company. Some are mostly words, others mostly numbers. However, most business cases that product managers create aim to persuade their company to develop or enhance a product.

You can read all the articles in our Product Management Journal – Business Cases by signing up for free here.

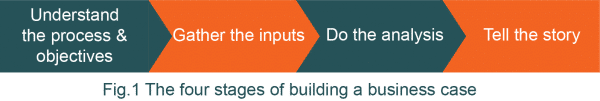

A business case is a fundamental part of the product development process. It is normal for business cases to go through a series of iterations of increasing rigor throughout the product innovation stage. A ‘high-level’ business case is often further refined in the lead-up to development, as assumptions and costs become clearer.

When you set out, you may not know whether your business case will ‘stack up’. However, by the time you finish, you should have a detailed understanding of the business opportunities and risks for your product.

Understand the objectives

Most business cases start as a business idea validated with some market research, anecdotal customer evidence, or gut feel. The first step is to find an executive sponsor who cares about your success and who can provide guidance and support throughout the project. Your next step is to find out what has to be done by when, the scope and constraints you have to work within, and the process to follow. The output of this stage should be a plan that shows how you will develop and deliver the final business case. You may have to do this yourself, or if you are lucky, you may have a project manager to support you.

To build the plan, you need to be able to answer the following questions:

- Who needs to be involved in the team to produce the business case, e.g., Finance?

- Is there a prescribed process or template to follow?

- Are there any key dates for which the business case must be ready, e.g., a gate meeting?

- Who are the key decision-makers, and what’s important to them?

- What deliverables need to be produced, and by when?

- Are there any generally understood criteria that must be met, e.g., all projects need to pay-back within 2 years?

Understanding how the people who judge your business case will make their decisions is vital. If you don’t know what their criteria are, it’s like playing darts on a board without numbers. There are different business benefits to aim at but, you don’t know which ones to target. It’s unlikely that you’ll ever get a perfect view of the relative importance of each business benefit, but the more you know, the more you can craft your business case towards them. You may be able to find out what’s important by talking to decision-makers directly by talking with your stakeholders or the business case process owners. Equally, they may not want to reveal anything and bias your case, which doesn’t mean you shouldn’t dig anyway! If all else fails, speak to your executive sponsor to understand their perception of stakeholders drivers.

Gather the inputs

The second stage is about gathering the inputs you need to prepare the business case. This is the data you will use to construct your financial model and word-based justification. Some of this will be known, but the rest of it may need to be assumed. In a small business, you must do much of this yourself; in larger businesses, there are lots of other people to talk to. This is your opportunity to gather evidence from within and outside the business to support the assumptions that are made. This evidence must convince people that any assumptions are realistic, credible, and objective.

For business strategy and market input you will need to talk to:

- Anyone with access to market forecasts or research reports.

- Anyone with access to competitor info (or research this yourself).

- The strategy team (or whoever owns the business strategy).

- Product Marketing, to learn how your product will be positioned against other products and propositions.

- Marketing, to learn about any other planned launches or promotions that might compete for resources. (This may provide you opportunities to align and grab some of their resources.)

- Business development, sales, and channel managers.

For sales and revenue input you will need to talk to:

- Relevant sales channels to get a view of the sales they believe they could make.

- Finance to get a view on factors such as churn or ARPU (Average monthly Revenue Per User).

- Other product managers to get their experience of take-up rates and also the assumptions they have used in their previous business cases.

For cost input you must talk to:

- Development and/or suppliers.

- Marketing to understand the cost of marketing activities such as launching and promotions.

- Support functions to understand the cost of providing support e.g., any recruitment required, any necessary IT system updates.

If your data and assumptions come from experts across the company or independent research they, become much more credible than facts and figures you ‘pull out of the air’.

In the best companies, you will be provided with an input pack from Finance that includes a set of data and assumptions already validated by the business and to be used in all business cases. Alternatively, there may be someone assigned from Finance to work with you on the business case.

In many business development processes, there is a domain representative assigned to all new product developments whose function is to provide expertise and input from their area, e.g. someone from Customer Services who understand their cost model, training needs, system requirements, utilization levels, etc… The key objective of this stage is to gather the data you will need to construct the business case, document any assumptions, and show buy-in from relevant teams.

Do the analysis

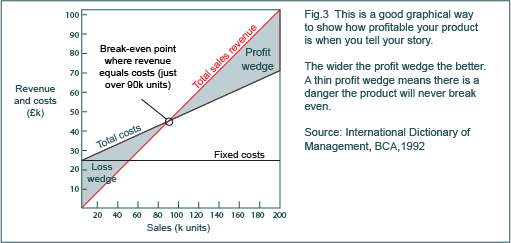

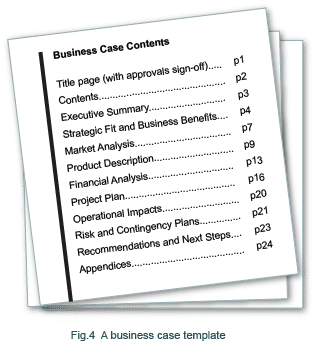

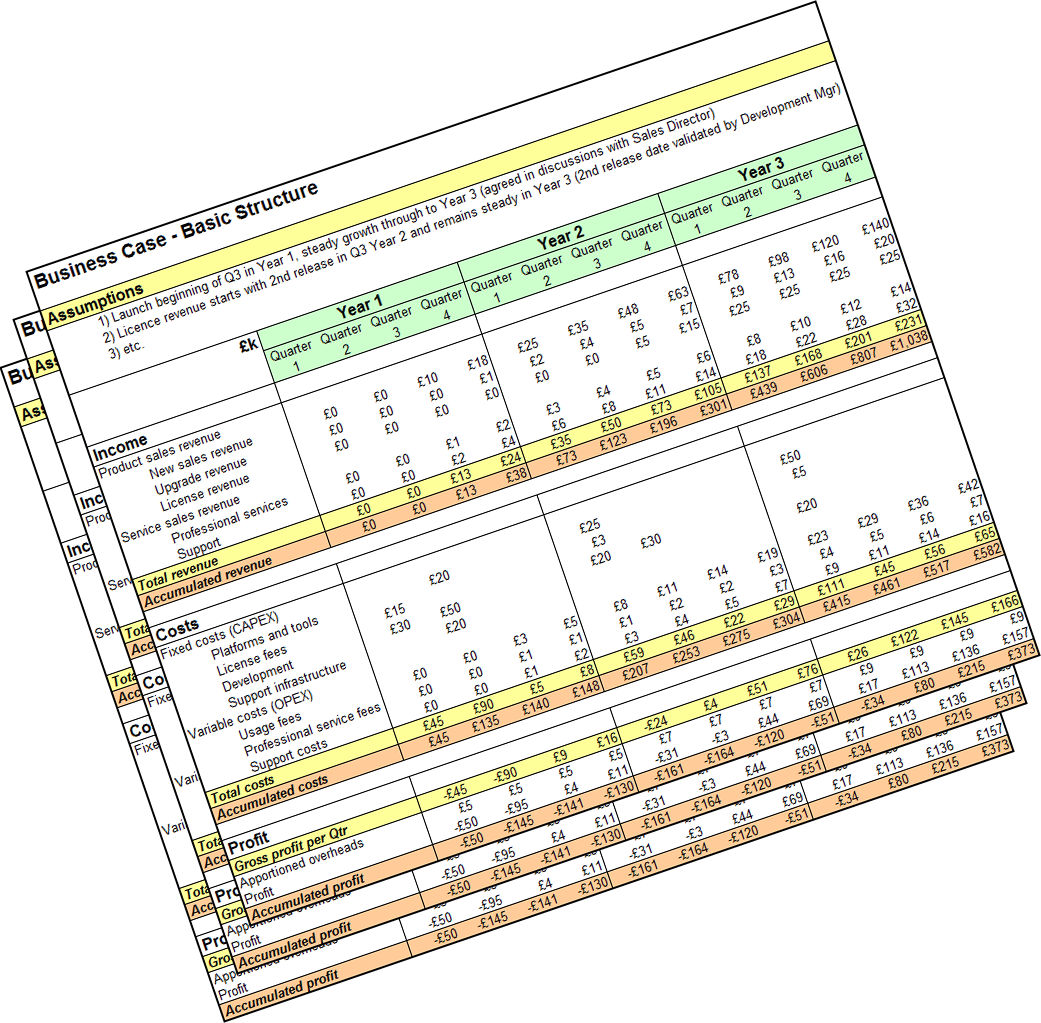

During the analysis stage you, study the inputs you’ve now gathered to build a detailed model of your product and your development project. The contents of a typical business case are shown in Fig 4. You will need to build a spreadsheet that will allow you to model various scenarios and understand sensitivity analysis. A typical business case financial model is broken down into a section on assumptions, a section on income (revenue), a section on costs and then a section that calculates the project value in terms of profit or payback.

Tell the story

The final stage of the business case process is to present or deliver the business case to the appropriate decision-maker(s). This may be through a presentation where you have the chance to explain your business case in detail or through the delivery of a document for review. The challenge is to keep the story clear, objective, and believable. If a decision-maker doesn’t understand it, they may not publicly admit this, but are unlikely to believe it.

If you can, it is often worth lobbying decision-makers before a meeting to understand if they are on-board, if they have any concerns and if they believe that input from their areas has been adequately represented. Fundamentally, a business case is a tool to sell your investment project (e.g. your new product) to the business. No-one can predict the future, so your success rests on the credibility of the case you make – the assumptions you use, the evidence you can gather, the support you line-up, the rigor of your analysis, and your personal credibility.

In conclusion

There are always many ways to spend the company’s money so most businesses have a standard process to produce business cases – with the aim of being able to compare one against the other and make it easy to say ‘yes’ to the right ones and ‘no’ to the wrong ones.

However, the true value of business cases is that they are the most rigorous assessment of a new product that is done during the development process and so force a level of investigation and analysis that should ensure (as far as is possible) the product is a success.

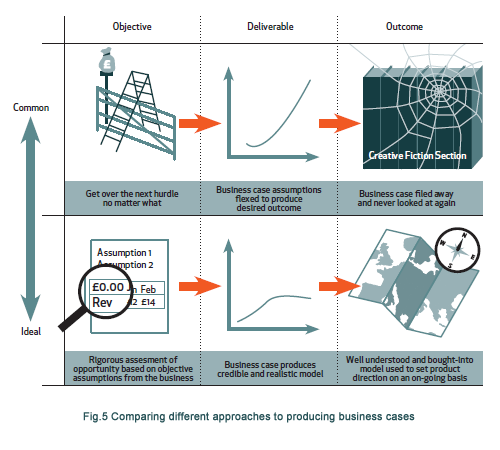

In an ideal world, the financial model, its assumptions, and sensitivities become a tool that can be used to manage the product through its life cycle. This is the ideal approach shown in Fig.5 above however in our experience the more common approach is often taken.

Industry comment

“In my experience, a business case is like a court case where the facts are documented but the final presentation is critical. Less experienced product managers often fail to clearly state their case and assumptions. They then get dragged off track into avoidable and damaging debates that unpick their underlying assumptions.”

Jonathan Wright, Director of Wholesale Products, Interoute