In this blog, Cyril Le Roux talks about the challenge product teams face when using Jobs To Be Done (JTBD) for the first time.

Cyril has over 20 years of experience in product management in enterprises, scale-ups, and startups across FinTech, eCommerce, and Marketplaces. He focuses on helping companies scale and build a robust product organization and is a Product Focus Senior Consultant.

A silent war is raging in the world of Jobs To Be Done (JTBD)

Every day on the planet, product teams struggle to use JTBD for the first time – they sometimes spend more time arguing about the model than focusing on the needs and aspirations of their users. This confusion arises because the term “JTBD” has evolved to encompass two related but dissimilar ideas.

The first interpretation of JTBD focuses on specific activities users engage in to achieve their goals. For example, sending marketing emails to a list of prospects or generating new leads might be considered JTBD activities.

The second interpretation of JTBD is broader, focusing on the overall progress that users are trying to make. In this view, JTBD is not just about specific activities but the larger goals and outcomes that users strive for. For example, generating new sales might be considered a JTBD progress outcome.

To help clarify the distinction between these two interpretations of JTBD and reduce confusion, we propose a naming convention: JTBD-A for activities and JTBD-P for progress. By using these terms, product teams can more easily communicate and agree on the specific focus of their JTBD efforts.

But first, let’s start at the beginning – which problems are your users trying to solve?

Why do you need JTBD as a product person?

Embracing the problem space instead of being solution-centric is crucial for success in product management.

While product and technology teams are typically tasked with finding solutions to customer problems, they often fall into the trap (and anti-pattern) of under-investing in problem analysis and focusing too much on solution ideation and development. This can lead to a premature commitment to a specific solution and a lack of understanding of the user’s true needs and pain points.

There are some early-warning symptoms you might recognize:

- Product teams become over-invested in their solution hypothesis or prototype. They present their best ideas to users, only to find users un-excited. And yet, the teams rationalize away the lack of delight and power ahead with their solution – ‘it must be right.’

- A relatively narrow range of solutions is being prototyped that all seem to be minor variations of the same concept.

The issue is that the team has fallen in love with its solution. But that kind of love is blind; it ignores the red flags and often results in failure. Therefore, when coaching product managers, I often repeat the mantra Intuit’s leadership team made famous: “Fall in love with the problem, not the solution.” To fall in love with the problem implies a lot more than being able to describe it. It requires feelings of user empathy that are only possible to experience by delving deeper into the user’s battles.

Falling in love with the problem pushes teams to acquire a richer understanding of the user’s background, capabilities, aspirations, hopes, and fears. It’s only when teams can feel the user’s pain as acutely as the user themselves that they start to understand their user. Then, and only then, do they stand a good chance of solving the right problem the right way.

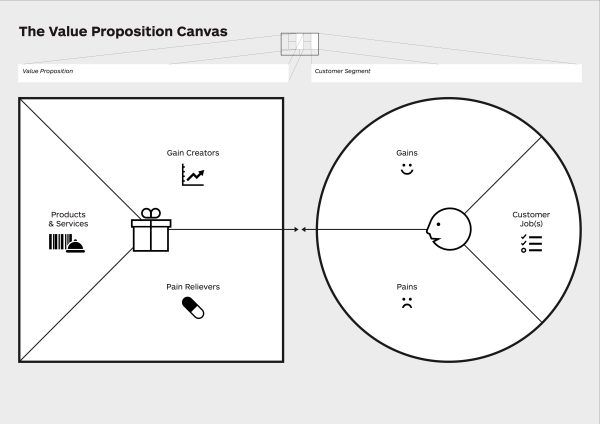

To get PMs started on that journey, I recommend the Value Proposition Canvas proposed by Alex Osterwalder. PMs begin on the right-hand side by listing the customer’s jobs to be done and then progress into the research of their associated job pains and gains. Solution ideation can then focus on reducing the pains or amplifying the gains. It’s about defining the problems that are most meaningful to users.

Osterwalder’s Value Proposition Canvas – © Strategyzer.com & Strategyzer AG

To illustrate, imagine a team working on a property marketplace app. Imagine they are looking at the consumer funnel and are disappointed with the conversion rate. Solution ideation without deep insight might point to usability improvements of existing features – like improving navigation or visibility of actions, such as “Contact the estate agent. ” While these may be important, they rarely yield drastic performance improvements in mature products. On the other hand, shining a spotlight on fundamental needs (or jobs to be done) can provide the team with much-needed insight.

Many users may be trying to relieve their boredom during a long commute by looking at pretty houses by the coast (for non-UK-based readers, this is a real thing that people do here). Or they want to compare their home interior with other properties on the market in their street (also a national UK pastime). They may be in the very early stages of their search and will spend six months browsing the market before starting to contact estate agents. Understanding what the user is trying to achieve is necessary to get a clear idea of what can be improved and by how much.

Listing the user’s Jobs To Be Done is about understanding what the user is trying to accomplish with your product. It should be easy, but teams spend a lot of time debating the level of abstraction of jobs. Using the example above of someone looking for a new home – you can decompose it into several layers – a hierarchy of needs:

- Be happy in my dream home ever after

- Live in my dream home

- Find my dream home

- Be informed about and review properties coming on the market

- Contact estate agents and visit properties

- See the price, location, and attributes of available properties

If you Google completed examples of the value proposition canvas, you will see that the JTBD side of the Value Proposition Canvas is often filled with statements that correspond to different levels of this hierarchy of needs. It is partly because there aren’t one but two schools of thought on JTBD. One led by the late Clayton Christensen and the other by Tony Ulwick.

Reno Gazette,

Reno NV, USA

Sat Aug 18 1923, p8

The origins of JTBD

The idea that people don’t buy a product but an outcome is a long-standing marketing concept that is at least 100 years old.

The Daily American, Somerset PA, USA

Sat Dec 12, 1942, p6

Research from quoteinvestigator.com identified an ad displayed in the Aug 18, 1923 edition of the Reno Gazette (US) that reads, “When you buy a rozar (sic), you buy a smooth chin […] when you buy a new suit, you buy an improved appearance.” Even the famous statement that “people don’t want a quarter-inch drill, but a quarter-inch hole” was mentioned in another ad from 1942 – this time for a life insurance product, predating Theodore Levitt, who made the quote famous decades later.

The issue with JTBD is that it looks like a concept that should have a unique definition. But it’s really two different schools of thought derived from the outcome-based view.

As a result, scores of product managers and marketers are confused about the proper definition of JTBD.

So, what are the differences?

Christensen’s JTBD is about Progress (hereafter called JTBD-P). He writes, “We define a “job” as the progress that a person is trying to make in a particular circumstance. This definition of a job is not simply a new way of categorizing customers or their problems. The choice of the word “progress” is deliberate. It represents movement toward a goal or aspiration. A job is always about making progress. It’s rarely a discrete event.”

JTBD-P sits nearer the top of the hierarchy of needs because they point to what people want to be like – for instance, appear successful, feel safe, and feel accepted. In one video, Christensen quotes an example of people ‘hiring’ a milkshake to relieve boredom on a long commute by car. This need prompts users to seek solutions that will fulfill their higher aspirations. As Christensen puts it, it is a pull model: “Customers don’t buy products or services; they pull them into their lives to make progress.”

Ulwick’s JTBD is part of his broader Outcome-Driven Innovation model and focuses primarily on Activities (henceforth called JTBD-A). For instance, listen to music, or restore the blood flow in an artery. He defines it himself as “a framework for (i) categorizing, defining, capturing, and organizing all your customer’s needs, and (ii) tying customer-defined performance metrics (in the form of desired outcome statements) to the Job-to-be-Done.” While it is possible to have an emotional job, it exists only because of the functional job. Instead of a pull model, a better solution is pushed to the user.

To paraphrase Alan Klement’s excellent article on the subject, the difference between the two models boils down to why consumers buy products. JTBD-P is about a positive change in your life, which may or may not involve work. JTBD-A is about the work the user wants to do with the product.

Taking our property app example from earlier, you can now see where each layer is positioned:

| JTBD-A Activities | See the price, location, and attributes of available properties |

| Contact estate agents and visit properties | |

| Be informed about and review new properties coming on the market | |

| JTBD-P Progress | Find my dream home |

| Live in my dream home | |

| Be happy in my dream home ever after |

JTBD-P or JTBD-A, which should you use?

JTBD-A is a particularly powerful concept to drive incremental innovation within existing product categories when used as part of ODI (Outcome-Driven Innovation) methodology. It allows surfacing pockets of underserved, overserved, and table-stakes needs, which are then mapped to corresponding segment opportunities that would otherwise be difficult to identify. When applied to cleaning the dishes, for instance, it will map out every step, measure how satisfied different categories of users are with the outcomes of each step and identify segments whose needs are unmet. For instance, if many users struggle to keep stock of dishwasher tablets or salt and rinse fluid, it would lead you to a self-replenishing solution. A dishwasher that keeps count of the consumables it’s using and how much it has left, ordering more automatically when needed. Each step in ODI builds on pre-existing concepts – while the complete system provides a simple-to-follow methodology that can be taught and applied easily.

JTBD-P is more about disruptive innovation and starts with the desired aspirational outcome. The example above leads you to think about freeing users from a clean-the-dishes activity. It immediately broadens the problem space to include avoiding the creation of dirty dishes. When JTBD-P is used in a Value Proposition Canvas workshop, it can lead to whole new product categories. But, on the flip side (and at least based on my experience), it also requires participants to be comfortable with high levels of abstraction.

In conclusion, which should you use? It is less about picking a side in this war and more about using the right tool at the right time. It largely depends on whether you are constrained to a frame that limits ideation to incremental innovation or whether you want to increase the potential for a more disruptive solution. Be explicit about whether you’re using JTBD-A, JTBD-P (or maybe a combination of the two – if that works).

P.S.

So, who invented JTBD?

In 1999, Tony Ulwick of Strategyn, introduced Clayton Christensen to his concept of Outcome-Driven Innovation derived from a Six Sigma approach of studying the underlying process. The term “Jobs to be done” didn’t yet exist – but would be subsequently introduced by Clayton in 2002 in his book, the Innovator’s Solution.

Interestingly, Christensen didn’t claim to have invented the term. In one of the book’s notes, he credited Richard Pedi, CEO of Gage Foods, for the expression while at the same time acknowledging Ulwick’s prior work on it. The JTBD concept was loosely defined then, but it stuck.

In 2005, Ulwick published “What Customers Want: Using Outcome-Driven Innovation” and refined the JTBD concept by focusing it on customer activities. 11 years later, in 2016, Christensen published “Competing Against Luck,” which also refined JTBD, but in a different direction to Ulwick’s. In the notes, he credited Rick Pedi and Bob Moesta for helping shape the Theory of Jobs To Be Done, with no mention of Ulwick this time. Exactly 3 weeks after the publication of Competing Against Luck, Ulwick also published a new book called “Jobs to be done, theory to practice,” which reiterated his interpretation.

Cyril Le Roux

Product Focus Senior Consultant

Join the conversation - 6 replies

Thanks Cyril, I enjoyed your review of these JTBD approaches.

My only experience has been with, what you call, JTBD-A. I have found the process (ODI) effective. That is, increasing the chances of developing the right capabilities.

Over 25 years of B2B product management, I’ve not really seen the war between the two approaches, but I have observed a lack of systematic approach to meeting market needs (over diving at big-customer-A’s latest request). I imagine either approach would add significant value to the majority product companies.

Do you agree, or is this war something you see in practice, as well as in principle?

Thanks for your comment, Rick.

I completely agree that both approaches work. The sort of ‘war’ I’ve seen was between passionate product managers and user experience managers arguing in a workshop what is the ‘right’ level of abstraction, i.e., JTBD-A or JTBD-P.

Since both methods have merits, the point is about recognizing that there might be a different interpretation and then aligning before a workshop on the approach to use.

It’s been a while since I last read “Competing Against Luck”. Honestly, it’s a bit disheartening to read about the “war” between JTBD-P and JTBD-A, as it distracts from what I believe are the core messages of the book: discovering a purpose that one may not fully realize about themselves or their customers, and aligning an organization around a purpose.

I understand how that discord can feel discouraging. At its heart, the JTBD concept is about understanding people’s deeper motivations and aligning your team around creating meaningful value. By keeping focus on that purpose—why customers “hire” a solution and how we can better meet their needs—we preserve the essence of the approach, regardless of the particular “school” we follow.

Perhaps I’m approaching this from the perspective of executable unity within an organization. From that viewpoint, are these really two separate schools of thought? I tend to view JTBD-P and JTBD-A as a mathematical vector: JTBD-P represents the direction, while JTBD-A represents the magnitude. Together, they enable an organization to align and execute by providing a clear direction and measurable progress toward that goal.

Referring to the property app example from the blog post, the job abstraction “Help customers find a dream home” at the JTBD-P level is more aspirational, aligning various business units around a shared vision. In contrast, “Help customers see the price, location, and attributes of available properties” at the JTBD-A level provides concrete, actionable steps for teams to follow when building the app.

Perhaps I’m approaching this from the perspective of executable unity within an organization. From that viewpoint, are these really two separate schools of thought? I tend to view JTBD-P and JTBD-A as a mathematical vector: JTBD-P represents the direction, while JTBD-A represents the magnitude. Together, they enable an organization to align and execute by providing a clear direction and measurable progress toward that goal.

Referring to the property app example from the blog post, the job abstraction “Help customers find a dream home” at the JTBD-P level is more aspirational, aligning various business units around a shared vision. In contrast, “Help customers see the price, location, and attributes of available properties” at the JTBD-A level provides concrete, actionable steps for teams to follow when building the app.