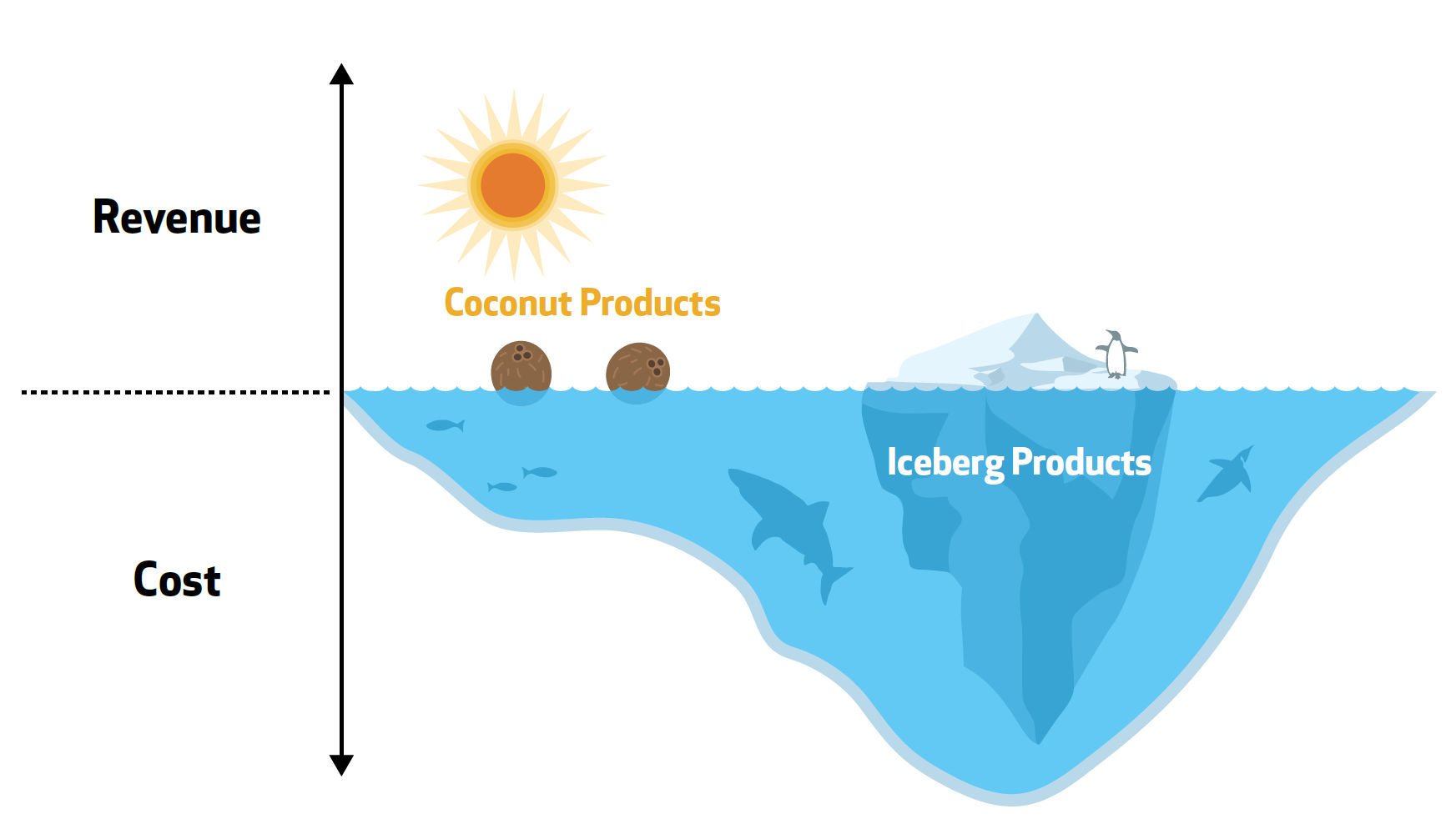

Do you have Coconut and Iceberg products in your business?

We’re all living longer. According to a UN report, the number of people over 80 will more than triple by 2050.

One of the paradoxes in product management is that there seem to be many more products launched than are ever withdrawn. So, are products living longer too? In the product management lifecycle, do they never get to the end-of-life stage?

In the fast-moving world of technology, we don’t believe that’s true – products are being brought to market and replaced faster than ever. Even so, many older products are left to slowly sink into oblivion. We call these Iceberg or Coconut products.

Coconut products don’t bring in much money, but it’s obvious that the cost to run them is not high, so it’s not worth the effort of picking them up and dealing with them. Some profitable revenue is coming in for little or no effort. The sun is shining, albeit not very brightly, in the world of coconut products.

Iceberg products are different. The outlook is colder. Like coconut products, they bring in little revenue and have few customers. But, what’s hidden from view is the enormous cost of running them. No one really knows if they’re profitable or not. Also, no one wants to spend the time and effort to find out. It’s easier to assume that someone else must have already checked the profitability. The conclusion is ‘leave well alone’ until something forces you to deal with them.

Unfortunately, that’s not necessarily the best approach.

Iceberg and Coconut products

Case study

A couple of years ago I was involved on the periphery of a merger between two big companies each with a large overlapping portfolio of products. The team I was in did some work to analyze the profitability of all the products in each company. We found about 400 in each but also worked out that 80% of the revenue came from about 10 products. The remaining 790 only brought in 20% of the revenue!

When we looked at the cost to the business of running these 790 products it was huge. Very few were profitable and we identified the following issues.

• Ownership (i.e. who the product manager was) was often unclear.

• For some, the sales materials were so out of date that no one was selling the product even though it was apparently part of the portfolio.

• Contractual agreements with customers were not always easy to find, so obligations and the implications for the support of customers and the products were unclear.

• For others, when there was an issue, the support team could only provide very high-level answers. No one had any experience of the product as they had long ago moved on to newer things. Support issues quickly escalated through to product management and some unlucky product manager spent days tracking down the answers from disparate people spread across the company.

• On other occasions, there was a sudden panic because some of the underlying technology that one of the products relied on was being changed. This required some development effort to keep the product running. This could hardly be justified based on the small number of customers using it. However, there had been no pre-warning to customers about withdrawing the product, so the development resource was shifted from working on something much more important to fix the issue.

There had been some half-hearted attempts to close down some of these products. But they often failed because one of the customers using the product was really important and no one wanted to upset them and jeopardize the relationship.

Although both businesses in the merger were profitable, there had not been any detailed work to understand the individual profitability of products. The reporting, processes, and focus were just not there. Many costs, such as support costs, were spread out across all products without a detailed understanding of the real cost per product.

Plus, there was little incentive for anyone to look at the rationalization of the portfolio. The glamorous work, the projects that got you noticed, was launching new products.

It wasn’t just the costs of running these products that were not tracked or recognized. The opportunity costs were also not considered. Having Development, Support and Product Management resources tied up on these products meant they couldn’t be working on new things.

No one recognized that there were so many iceberg products floating around nor their huge cost to the business. It eventually took many years, and a major program, to drive the rationalization and replacement of these products and services – at a huge cost.

Conclusion

Our view is that every product should have a product manager looking after it. And, every product manager should know whether their older products are coconuts or icebergs. That means having a clear idea of whether the product is profitable or not and how strategically important it is.

Many companies tackle this with an annual review of the whole product portfolio. This allows them to do some long-term planning about migrating customers from old products to new ones, withdrawing products, understanding strategic fit and tracking individual product profitability.

Don’t let iceberg products sink your business and may the sun always shine on your coconuts.

Ian Lunn

Director, Product Focus

Join the conversation - 6 replies

Very interesting read. I’m currently going through this with one of our customers. Thank you, very helpful.

We’re glad you found this helpful!

Very nice metaphor! Thanks for this picture.

If I understand right, coconuts and and icebergs are products which are not really managed (= free floating). So how would you call properly managed products in this picture?

(Why not boats or ships? They have a helmsman or even a captain 😉

Nice question It’s probably a ‘Cash Cow’. But for fun, to extend the analogy, it might be a “Treasure Island” product that’s visible and appealing like a coconut, with lots of treasures and revenue and known costs. This product would be both profitable and strategically aligned with the company’s goals, effectively-managed to maximize visibility, with known well-controlled costs.

Interesting read. The comment “No one had any experience of the product as they had long ago moved on to newer things” resonates. Add to that when people with product knowledge leave a company and there is no one left with enough knowledge to support/make changes/fixes, or even to make a priority call.

We’re glad you found this interesting, and thanks for sharing your thoughts!